Aerial view of the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens as seen from the southwest. Columns of ash and volcanic gas reached heights of more than 80,000 feet.

Courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey

On May 17, 1980, geologist Carolyn Driedger stood beneath a volcano she knew intimately — and one she was beginning to fear.

The summit of Mount St. Helens towered above, its graceful, snow-covered slopes gleaming in the sun. But her eyes were fixed on something else: a grotesque bulge protruding from the mountain’s north face.

“It was almost a vertical slab, swollen like a wound,” Driedger recalled. “It was clear this was an evolving situation.”

Her instincts were correct, her apprehension justified, though she had no notion of the extent of what was about to happen.

In less than 24 hours, the mountain she saw would be changed forever, the entire peak and north face would be gone, and a path of destruction would fan out across an area of 230 square miles. The eruption was the deadliest in U.S. history, killing 57 people, including a young geologist, David Johnston, whom Driedger was on her way to see.

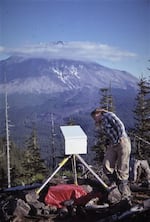

Carolyn Driedger peeks at the timelapse camera set up at the observation post known as Coldwater 11, during her visit with geologist David Johnston, May 17, 1980.

Mindy Brugman

This year marks the 45th anniversary of the eruption, and Driedger’s personal recollection and the photos she snapped that weekend in May 1980 are haunting reminders of what was lost, but also a reason to reflect on how much scientists and response teams learned from that disaster.

Driedger was 27 in 1980, working for the U.S. Geological Survey in Tacoma, Washington. Like many young scientists drawn to the Pacific Northwest, she had spent weekends climbing the region’s Cascade peaks. She’d climbed St. Helens twice and had even camped on its then 9,677’ summit.

She described the mountain as a “beautiful princess of a volcano, with a pointy, cone-shaped top — somewhat reminiscent of Mount Fuji.”

But this trip was different. She had come to help glaciologist Mindy Brugman with glacier surveys — and to rendezvous with a young but seasoned volcanologist named David Johnston.

Johnston had become a familiar face in the months since Mount St. Helens began rumbling. He had become a favorite source for news reporters, eager for any insights into the mountain’s volcanic activity.

As Driedger and Brugman bounced up rough logging roads to a remote observation post on the north side of the volcano known as Coldwater II, they could hardly have imagined it would be the last time anyone would see Johnston. His name would be forever connected to the mountain — marked by his final radio call as the eruption began: “Vancouver, Vancouver, this is it.”

But that story had not yet been written when Driedger visited him the evening of May 17, 1980.

Mount St. Helens the day before the eruption, May 17, 1980, as seen from the observation point known as Coldwater 2.

Carolyn Driedger / USGS / OPB

The last conversation at Coldwater II

The mountain had stirred to life earlier that spring, drawing national public attention. The U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Geological Survey and local authorities scrambled to assemble a response team while television crews swarmed the area. The public crowded behind barricades, hoping to catch a glimpse of lava or smoke.

“Everybody wanted to see some action,” Driedger said. “People were making T-shirts that said things like ‘Yeah, sure,’ kind of daring the mountain to do something.”

Media coverage focused on the mountain’s most colorful figure: Harry Truman, the 83-year-old innkeeper who defiantly refused to evacuate when officials established a “red zone” exclusion area around the volcano.

But a few reporters turned to Johnston for insights on the pending eruption. Despite his humble nature, he issued grave warnings.

“Right now there’s a very great hazard due to the fact the glacier is breaking up on this side of the volcano, the north side, and that could produce a very large avalanche hazard,” he told a TV news reporter. Then he added with a nervous chuckle: “This is not a good place to be standing.”

Johnston hadn’t been scheduled to be at Coldwater II, but had agreed to take the Sunday shift for his assistant, Harry Glicken.

The four young scientists spent hours on the ridge, talking shop, trading stories. Driedger snapped photos — of the trailer, the scientific equipment, the mountain, and Johnston himself.

“Here was this great guy who was watching over the volcano,” Driedger said. “We were a little starstruck.”

The first image shows Johnston seated in a folding camp chair, jotting measurements into his field notebook. He must have heard the shutter of Driedger’s camera snap. He looked up at Driedger and smiled. Her camera clicked again. It would be the last photo ever taken of David Johnston.

But even amid the calm, Johnston made a grim observation.

Driedger recalls him gesturing toward the bulge on the side of the mountain.

Four miles away from the mountain, their position was just outside of the evacuated “red zone.” In theory, they were safe if the volcano erupted straight up into the sky. But Johnston was concerned about another possibility: a lateral blast coming out of the side of the mountain.

Driedger recalls him describing a massive explosion being released from the mountainside, rolling across the valley in front of them, and crashing right over the ridge where they stood.

“I think we were just in disbelief,” she said.

The weather was clear, the evening calm. Driedger and Brugman had brought sleeping bags, planning to camp and enjoy the view and Johnston’s company. And besides, the drive back to headquarters in Vancouver was hours of backroads. Driedger wanted to stay.

But as sunset approached, the mild-mannered midwestern Johnston grew firm.

“This is not the safest place to be,” he insisted. “We should have as few people here as possible.”

Driedger recalls detecting an undertone of fear in his voice. Johnston had shared a story with them about being caught on an Alaskan island during an eruption, describing rocks pelting a metal roof as he was stuck waiting for an evacuation helicopter.

Reluctantly, Driedger and Brugman left Coldwater II around 8 p.m.

“I was crestfallen,” Driedger said. As they descended the mountain, she turned for one last look.

She snapped a few final photos of the volcano, silhouetted against the darkening sky.

“You could see the bulge on the northern horizon over Silver Lake,” she said. “These are probably some of the last photos taken before the eruption.”

In sending them away, Johnston had just saved their lives.

When the news broke

The next morning, at 8:32 a.m., Mount St. Helens erupted. Just as Johnston had predicted, an earthquake shook loose the bulge, creating a massive landslide, releasing an inferno of superheated gas and rock that swept down the mountain, across the valley, and rolled like a tsunami over the outpost of Coldwater II.

Mount St. Helens erupted at 8:32am, Sunday May 18th, 1980. It exploded sideways first, in a massive lateral pyroclastic blast, then a column of gray ash began to boil upwards, rising as high as 80,000 feet.

US Geological Survey

Johnston has just enough time to pick up his radio and alert headquarters: “Vancouver, Vancouver! This is it.”

At that same moment, Driedger and Brugman were driving back toward the volcano when they saw something unimaginable: a dark cloud boiling from the north face of the mountain.

“We asked each other, ‘What is happening at the volcano?’” Driedger recalled. “And I think we both said, ‘I hope Dave is okay.’”

They wouldn’t learn his fate until later that day.

Returning to the headquarters in Vancouver, they immediately pitched in to help receive and disseminate information as the eruption continued. They took incoming reports from field observers and relayed updates to the press.

When rescue helicopters couldn’t reach Coldwater II, the scope of the disaster came into focus.

“I could see the faces of the observers — totally white,” she said. “I knew then this was unlike anything we had anticipated.”

Legacy in the ash

When the mountain blew, entire landscapes were obliterated. Ash blanketed highways, forests, and towns.

“The ash destroyed everything,” Driedger said. “The leather on your boots, the buckles, belts, cameras, glasses.”

In the months that followed, Driedger returned to the mountain. With rulers and ice probes, she and her team documented the ash, measured glacial loss, and assessed the destruction.

Scientists found the mountain’s landscape transformed. Charlie Crisafulli recalled “seeing everything that had once been green was now shades of gray.”

Courtesy of USGS

She felt a rawness, an emotional loss of stability. Before May 18th, the snow-capped mountains of the Cascades were places where she would recreate, beautiful, silent sentinels on the horizon of Northwest cities like Seattle and Portland.

“These mountains — we thought of them as eternal, as benign, as the defining features of our beautiful Pacific Northwest,” she said. “This felt like betrayal.”

The eruption of Mount St. Helens was a defining moment for Driedger. Now a scientist emerita with the USGS Cascade Volcano Observatory, she’s dedicated her career to ensuring that what happened on Mount St. Helens would not happen again — at least, not without warning.

In the 45 years since the eruption, Driedger has helped disseminate scientific information on volcanic risk and develop response plans.

“Being involved in volcano hazard working groups has been my healing, my catharize,” she said.

Today, a quiet web of seismographic stations, scientists, emergency planners, and officials monitors peaks like Mount Hood, Glacier Peak, and Mount Baker — an infrastructure that didn’t exist before 1980. The eruption reshaped how scientists and officials prepare for volcanic disasters, according to Driedger.

“Mount St Helens was a wake-up call,” she said. “It proved the power of having a good dynamic between scientists and public officials.”

View of Mount St. Helens during minor eruption, two years after the major eruption on May 18, 1980.

Lyn Topinka / OPB

Still, Driedger said, preparing for volcanic eruptions remains one of science’s great challenges.

“Eruptions are so far outside normal human experience, people struggle to comprehend them. There’s nothing like a volcanic eruption to open that window, just a little. But after it’s over, the window closes again. And people forget,” she said.

The events on Mount St. Helens 45 years ago feel like yesterday to Driedger, but she points out many people in the Northwest have only known the mountain as it is today, a beautiful place to recreate. But Mount St. Helens and the other Cascades are not extinct volcanoes.

“They are just sleeping, and we know they will erupt again,” Driedger said. “And that within a few days, even hours, we could move into an eruptive state.”

Her work has taken her around the world. During this anniversary of the Mount St. Helens eruption, she will be in Iceland, studying the interactions of glaciers and volcanoes glaciers. Her local work is currently focused on Mount Rainier. But Mount St. Helens is always the place where it started.

“The process of nature is going to happen; we just need to pay attention,” she said. “And that was what David Johnston was telling us. Pay attention. That’s the message he would want us to carry forward.”